The Archipelago Network is an initiative for research and documentation of endangered audiovisual heritage and material knowledge on the Cyclades islands, located in the Aegean sea. Through its archival preservation activities, interdisciplinary residencies and public programs, it takes up the Cycladic archipelago as a laboratory for field research and knowledge production, addressing pressing social and ecological questions of our time. Tina Marinaki invited Jacob Moe, founder and lead researcher of Cycladic Archipelago, in a conversation around the initiative’s story and concerns as well as their methodological approach. The interview was first published on Archisearch The Paper Edition 6.

The organization’s team, based in Syros and Athens, consists of staff with extensive experience in audiovisual preservation and production, implementation of residency programs and cultural activities, as well as large-scale project management and coordination. An array of external advisors provide expertise on an ad-hoc basis in the fields of digitization, intellectual property law, and discipline-specific information related to individual projects.

Jacob Moe, founder and lead researcher of Cycladic Archipelago, was born and raised in New York. However his relationship to Greece started through his earliest memories as a child as his mother, a philhellene and professor of Modern Greek studies, chose to speak the language to him as he was growing up.

After he grew up he became a documentarian, archivist and literary translator. He is co-founder of the Syros International Film Festival and has produced various community-based film and radio documentary projects in the USA, Brazil and Greece.

He is currently lead archivist of the Archipelago Network, which was founded in 2019, though as he explains “the impetus and ideas leading up to it had been in the making several years before that”.

– What were your strongest memories from Greece?

Around 1998, my family moved from an apartment in Manhattan’s Morningside Heights neighborhood to a house in a pistachio grove in Aegina’s main town. I remember the annual pistachio harvest, the open horizon of the sea at all sides, and the process of assimilating. As I attended the local elementary school, I began learning to read and write Greek. I remember being particularly resistant to the placement of accent marks on words: no such thing existed in English, and it felt completely unjust to me to only learn new words, but to have to know exactly where to place the emphasis on each syllable.

– Tell us about the initiative of the Archipelago Network. When was it founded and why? What are the initiatives of the organization?

The initiative was founded in 2019, though the impetus and ideas leading up to it had been in the making several years before that. Having organized the Syros International Film Festival since 2013, I came into contact with different forms of local audiovisual heritage on the island: forgotten home movies, amateur films, and rare documentaries which friends and acquaintances suggested we screen. I began to realize the urgent need to preserve and document these materials, which surpassed the mandate and capabilities of SIFF; and in discussions at the time with colleagues from different backgrounds – historians, lawyers, anthropologists, artists, activists and artists – the proposal to create a living archive out of this material, connecting Syros with other Cyclades islands, and with the broader Mediterranean region, came about.

Since our activities are implemented according to island and theme specific focuses (traditional trades such as boatbuilding and pottery, for example, or knowledge concerning the natural environment) we also work on a case by case basis with a wider network of specialized consultants.

– You are also the co-founder of the Syros International Film Festival.

My first visit to Syros, in 2006, was something of a coincidence. A family friend invited us to visit the island that summer, and we kept returning after that. As the summers passed, I began studying film at university in Los Angeles; then I began working on documentary films in the area as a production and research assistant.

So my curiosity for Syros, with all of its cultural, social and environmental particularities, coincided with my growing understanding of film as a tool for social documentation and engagement with reality.

Upon graduating college in 2013, I started the Syros International Film Festival with a friend of mine, Cassandra Celestin, based on a shared instinct: we wanted to place the landscapes and communities of Syros into conversation with a playful and unconventional approach to film programming, combining different styles and genres by way of a single thematic focus.

– What can we learn today from traditional boatbuilding?

Wooden boatbuilding was fundamental to the development of Greek shipping and maritime trade for centuries; it was these very boats that sustained the people of island Greece for millennia through the circulation of goods, people and ideas.

During our project documenting traditional boatbuilding on Syros we digitized hundreds of archival photographs and documents from five active boatyards on Syros, produced a series of documentaries, and worked with ethnographer Maurizio Borriello and architect Iris Lykourioti on research outputs. These collected materials seek to provide material evidence for the development of the technique and art of boatbuilding, advocating for its continued existence in the future.

Years before sustainability and the “blue economy” were at the forefront of development agendas, traditional boatbuilding provided a model for naval architecture in dialogue with and respectful of the marine environment.

The question now is how to integrate modernized management and construction technologies into this existing knowledge system, in a way that renders the craft a financially viable and competitive alternative to less sustainable naval architectural methods and materials for boatbuilding: fiberglass hulls, for example, which are completely non-recyclable.

– How did your engagement with Sifnos begin?

Our projects often begin as a response to a particular need, expressed by stakeholders involved on a local level with existing initiatives.

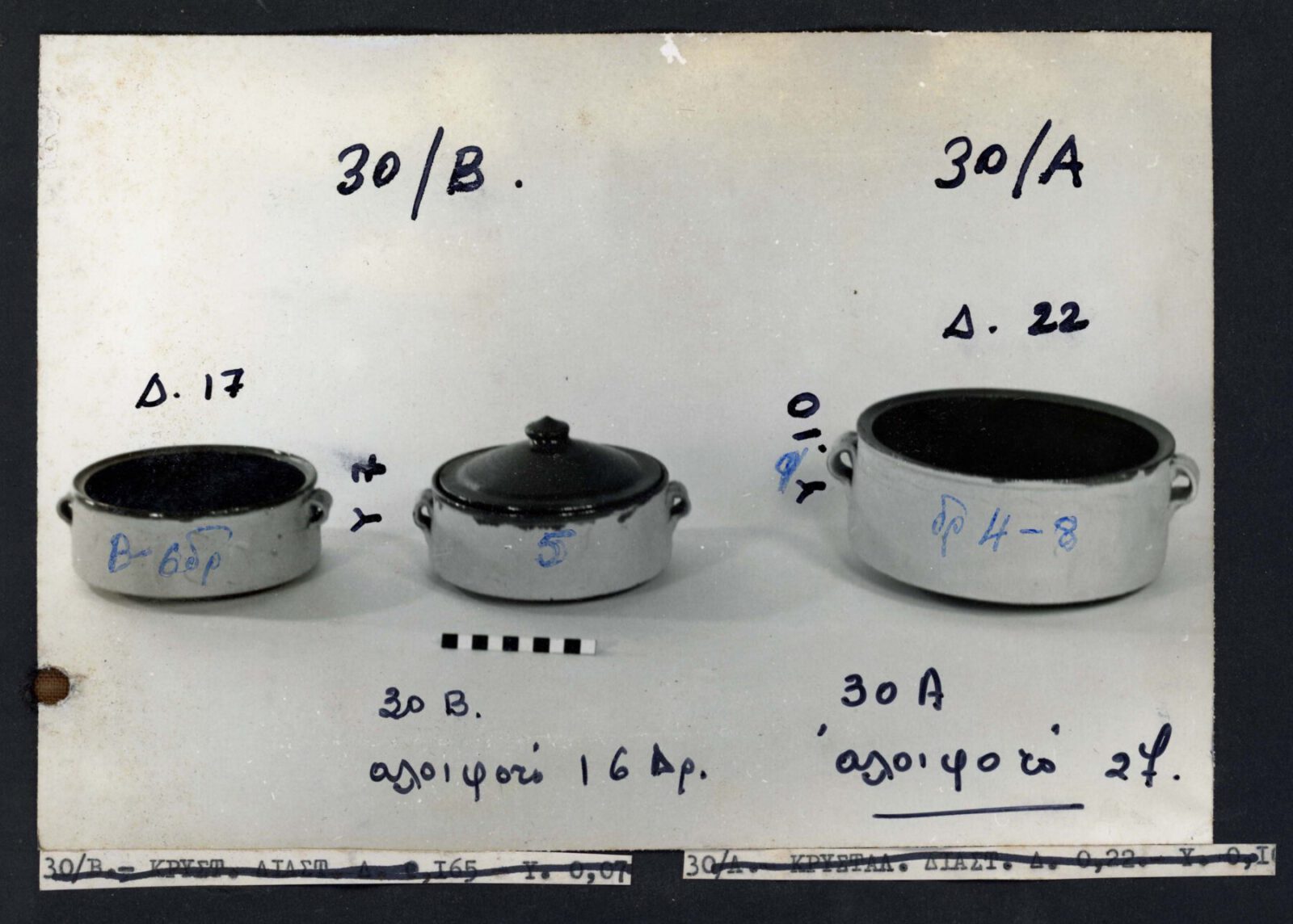

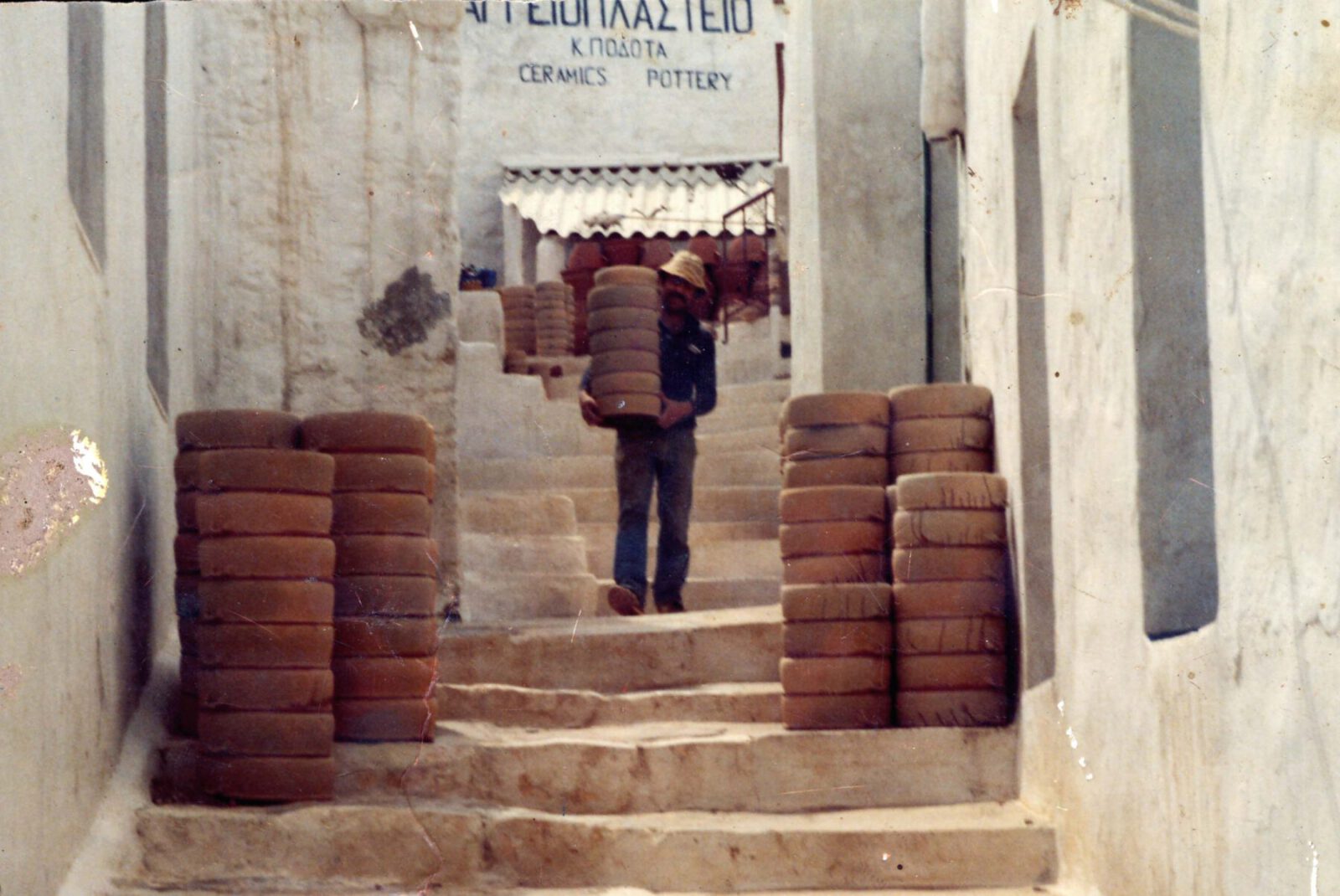

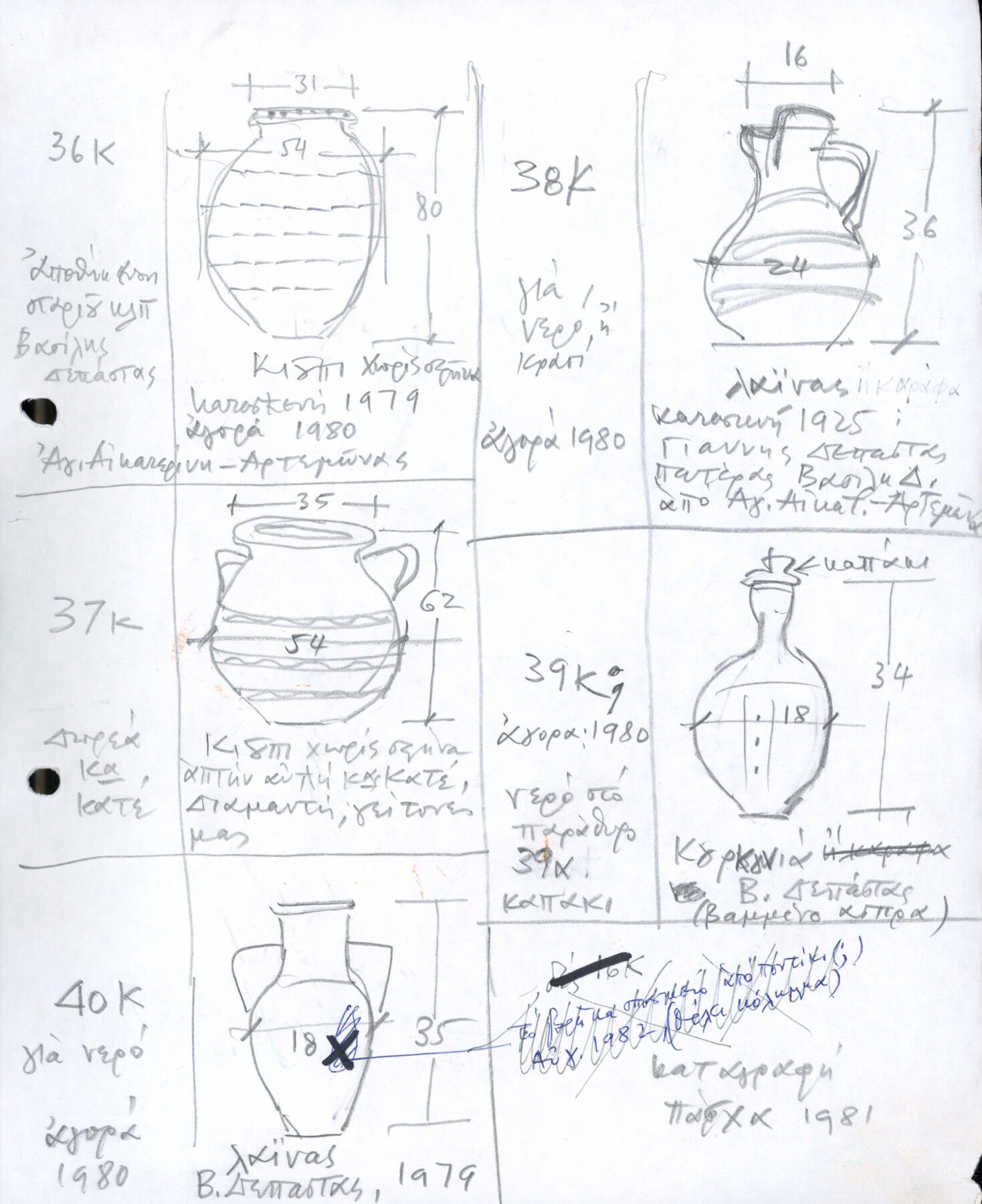

In the case of Sifnos, we were approached by community members there concerning documentation needs related to the establishment of a Museum of Pottery on the island: the organization of a photographic archive belonging to the Sifnos Potters’ Union, and detailed film documentation for each of the island’s existing pottery workshops.

The island is exemplary not only for its centuries-old pottery craft, but also for active community groups promoting the island’s unique environmental heritage, championing traditional knowledge while seeking more sustainable forms of water consumption and touristic development.

– What does the program involve?

Each of our archival projects begin with three core interrelated layers: archival documentation, the production of documentary films, and interdisciplinary research with a public humanities focus. In Sifnos, we digitized hundreds of photographs and documents, including a remarkable collection of material belonging to the late artist and architect Cosmas Xenakis, whose collection of Sifnian ceramics comprises the core of the Museum of Pottery on the island; we produced a docu-series consisting of thirteen short films, one for each of the active pottery workshops; and we are currently working with architectural historian Ioanna Theocharopoulou and curator Lydia Matthews on the production of a monograph and visual essay based on different aspects of the archival documentation collected on Sifnos. Upon completion of the project all this material will be available under an open access license for public use.

-In a time when sustainability and materiality are important in construction and architecture, the interest in transforming clay into structure rises. How can we engage the knowledge and craftsmanship of the past and re-invent them/ re-introduce them in the present?

On a personal level, my interest in audiovisual archives is linked with knowledge production and advocacy efforts for social and environmental justice.

In this sense, the choice to highlight the craft of pottery making on Sifnos is also an effort to raise awareness of its uniqueness and fragility in the present, and map out ways to support the evolution of this craft for future generations.

Part of that involves slowing down enough in order to re-learn traditional forms of knowledge that have always been in harmony with nature, to a certain extent. To give you one example, potters in the village of Platys Gialos were explaining to me the particular ways they harvested branches from juniper trees and brush on nearby mountains, so that they would grow back season after season. They used these dried branches to fire their kilns and make pottery; so it was mutually beneficial to the potters for the trees to exist in perpetuity.

I would argue that reintroduction of these practices into the present, in our era of climate emergency, is just as important as developing new technologies – for energy production, carbon capture, sustainable building materials, etc. And it is worth exploring ways to link these traditional and time-tested practices, which are by their very nature about adaptability and resilience, with the cutting edge technological developments of today.

-What is the role of craftsmanship today? Why is it important to preserve? What does “local” and “tradition” mean to you?

I’ll give you the example that Antonis Kalogirou, a potter in Artemonas village of Sifnos, told me in our interview together. The “flaros” is a ceramic chimney-top made in Sifnos, and quite characteristic of the island. Today, it is considered a “traditional” object. But according to Antonis, it was first introduced to the island just about a century ago. And since then it progressively evolved over three generations of potters to become an indispensably Sifnian creation.

So this begs the question: what constitutes “traditional” in pottery? Something that was made 50 years ago? 100? 1000? Tradition is both completely subjective, and always evolving. And once you understand that, it allows you to use it as a resource for the future, and not a standard to be inflexibly upheld. It is situated knowledge, encoded in this case in the form of objects.

Traditional pottery is an antidote to a future largely populated by mass produced objects and unsustainable materials.

– Can you tell us more about the two interregional projects: “Communities Between Islands” and “Mirrors: Trans-Mediterranean Archive Dialogue.”

We have purposefully embarked on thematic documentation projects in the Cyclades in parallel with international cross-disciplinary collaborations of a broader geographic scope, seeking to transpose localized forms of knowledge in the Cyclades onto a wider context.

“Communities Between Islands” is one such project, which involves a cycle of artistic residencies between 2023-24 on Corsica, Sardinia and Syros. Working primarily with time based media, nine selected artists will produce work and host workshops on each island related to different environmental issues, in collaboration with local arts organizations.

“Mirrors” involves an exchange of knowledge and best practices concerning archives and open access protocols between Archipelago Network, Cimatheque (a film archive in Cairo, Egypt) and UMAM Documentation & Research (a human rights NGO in Beirut, Lebanon), resulting in a series of community workshops in each location and a handbook of legal and ethical tools for community archives.

-What are your future plans for the Archipelago network?

It’s hard to say when each project begins and ends; since everything we do is open access, the end of a project is also a new beginning, after which archives and research outputs can be activated in new contexts by communities and online audiences.

In the near future, we will be publicizing results from our multi-island project “Maritime Trades of the Cyclades,” which traces traditional boatbuilding, small scale fishing and seafaring practices on the islands of Amorgos, Koufonisi, Paros, Santorini and Syros. We’ll then design a series of public events and actions on each project island in collaboration with our various local partners; that’s when the life of the project begins.

READ ALSO: Leisure - or philosophical – architecture | A talk with Dimitris Potiropoulos and Danai Makri