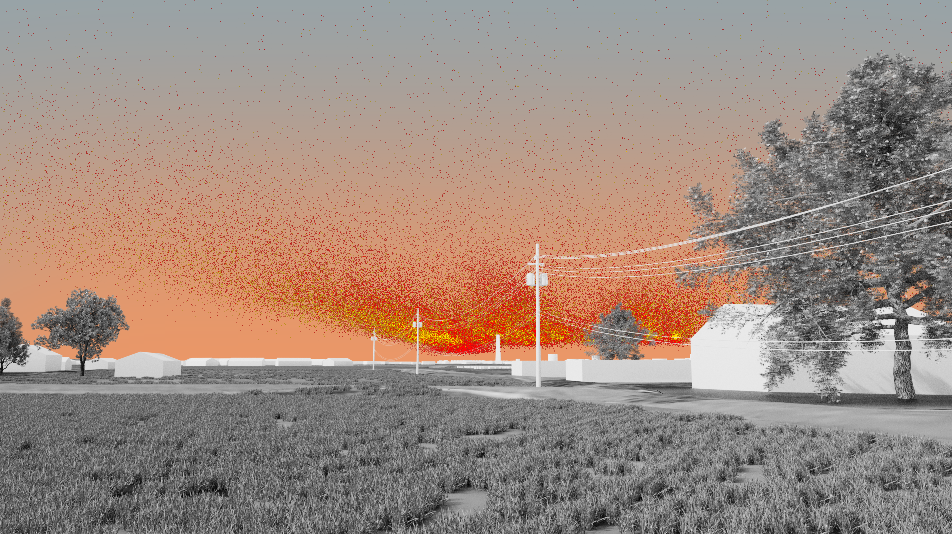

A stretch of the Mississippi River once called ‘Plantation Country’ is now the ‘Petrochemical Corridor’, known to those who breathe its toxic air as ‘Death Alley’. Using advanced techniques in cartography and fluid dynamics, the latest investigation by Forensic Architecture (FA) supports ongoing and future action against further industrial expansion by local community activists RISE St. James and other groups of local activists across the region.

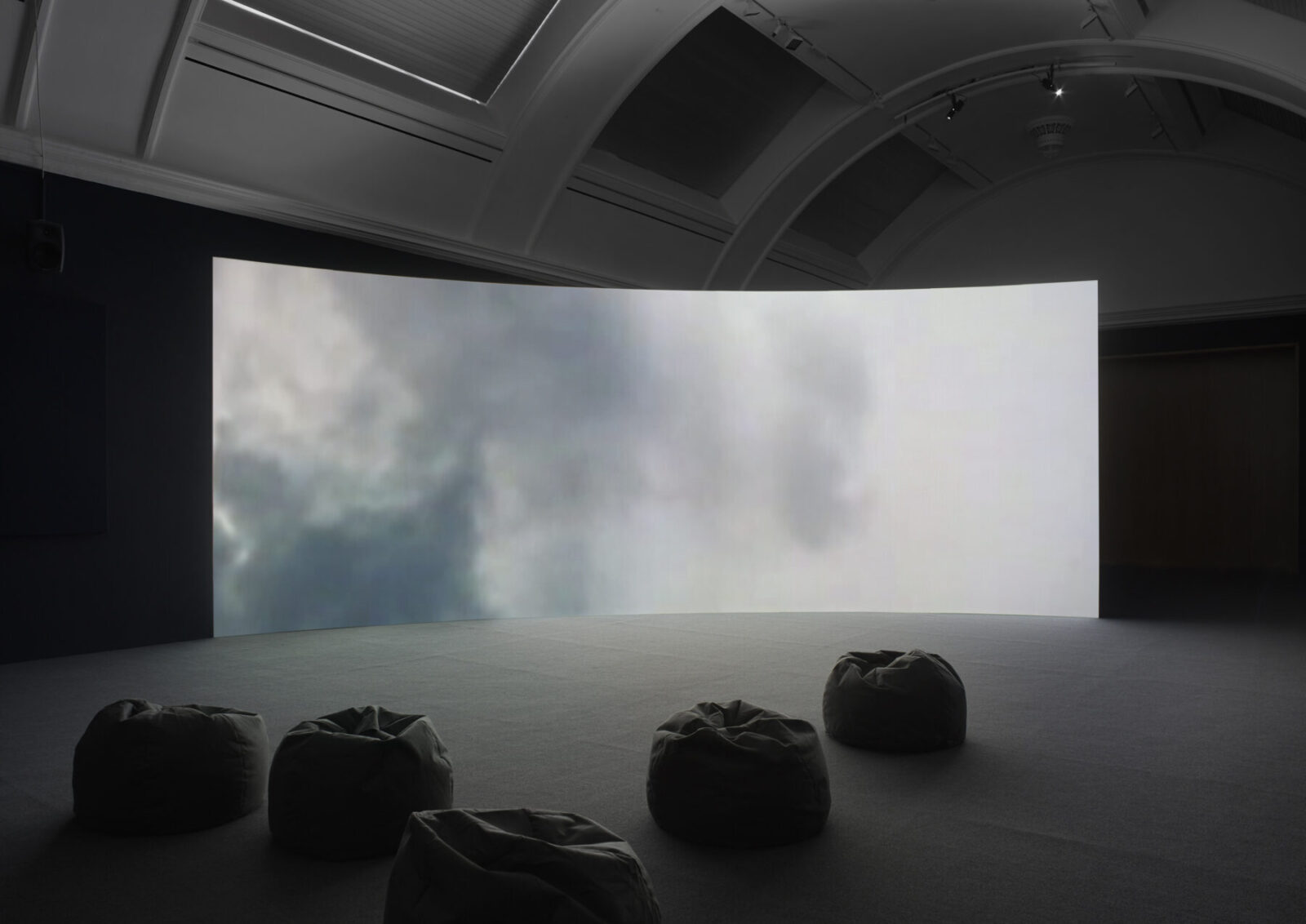

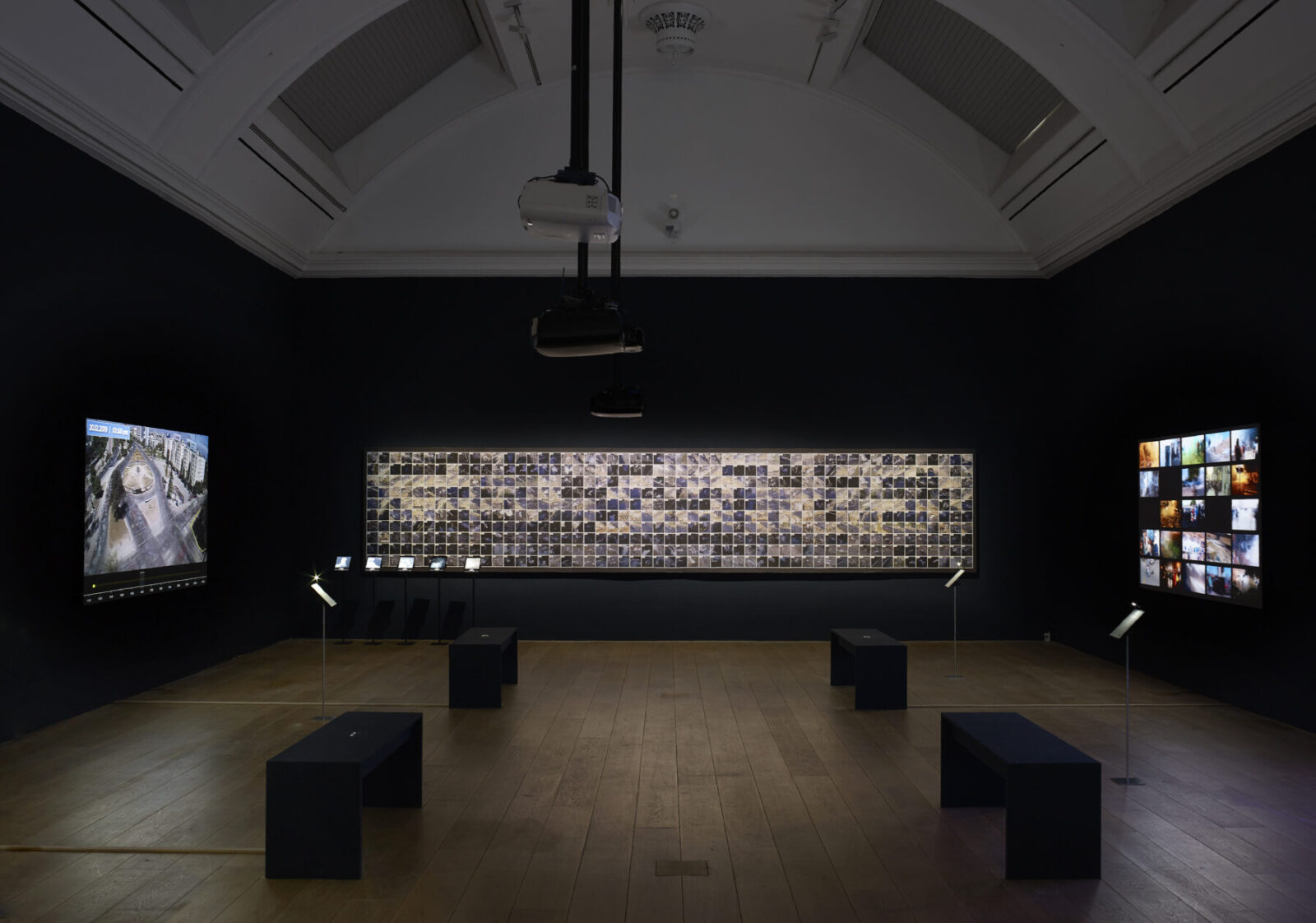

The project launches on 1 July 2021 at the opening of FA’s exhibition Cloud Studies at the Whitworth, part of the Manchester International Festival.

-text by Forensic Architecture

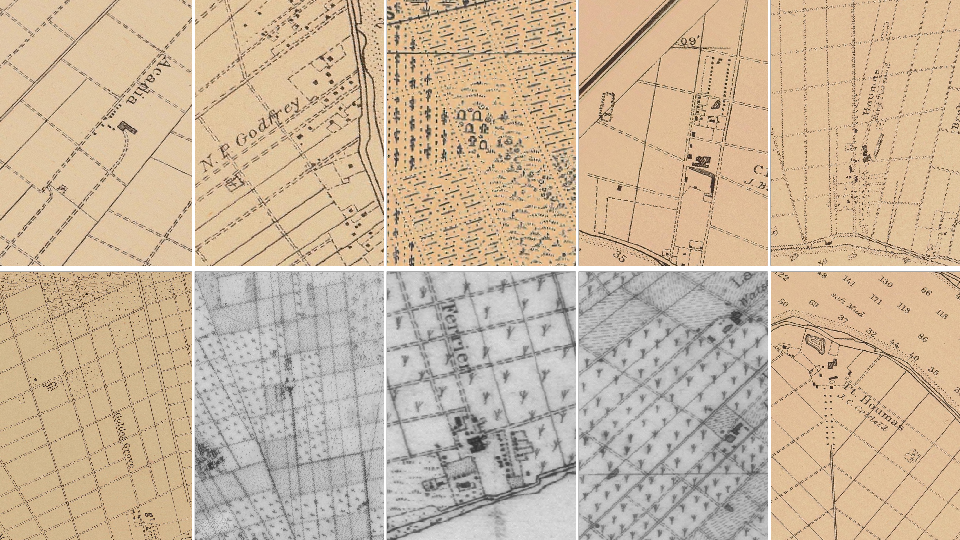

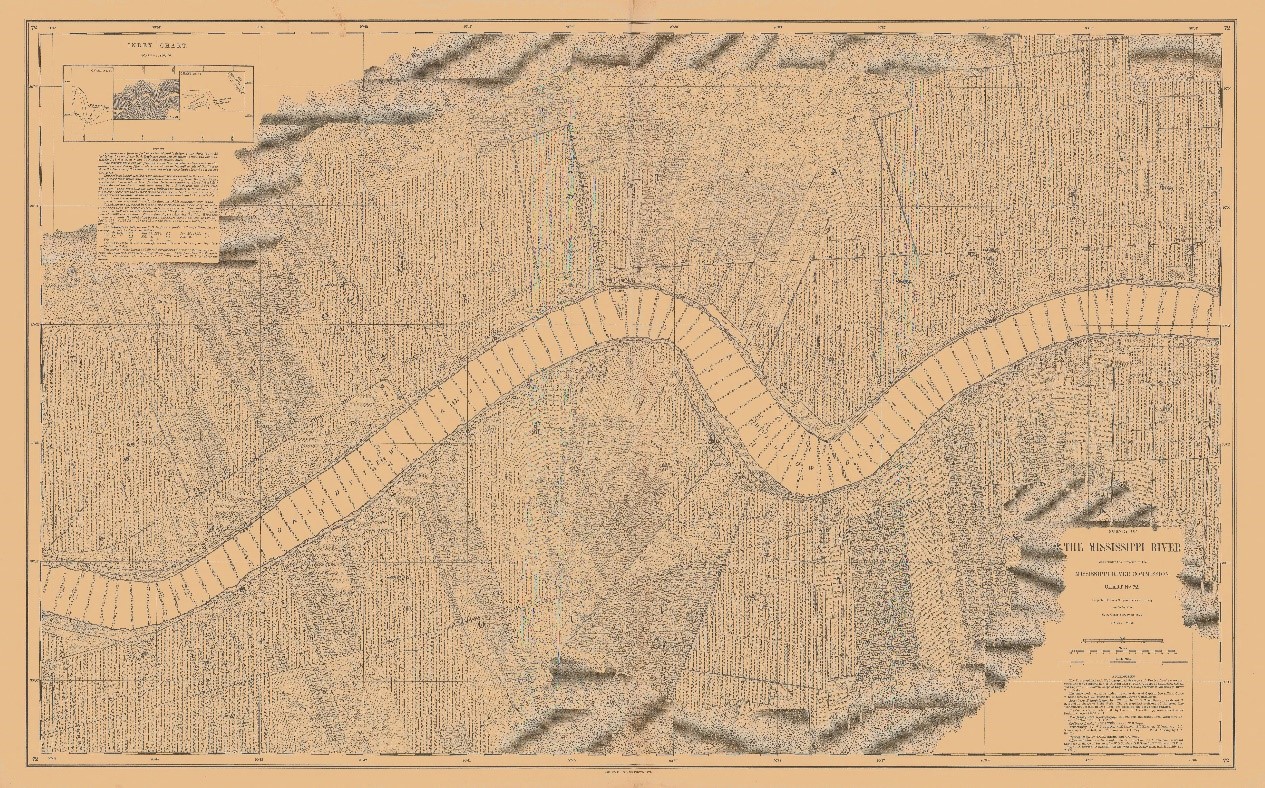

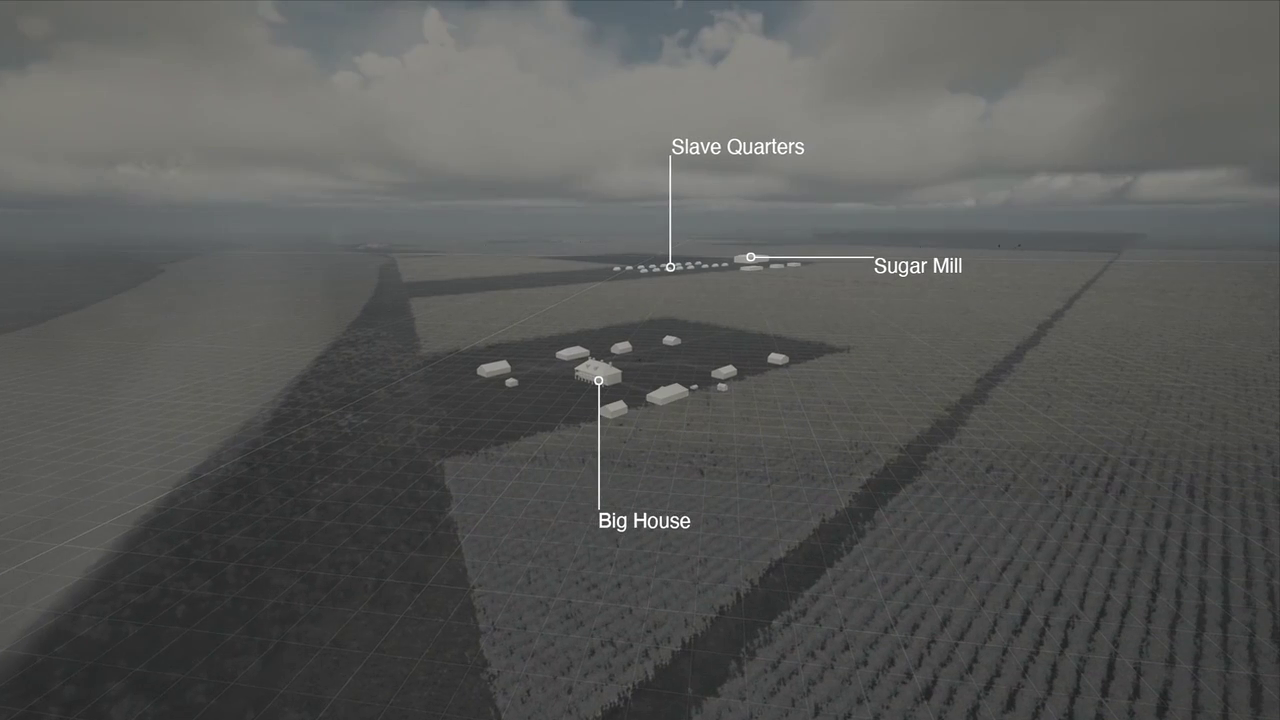

Forensic Architecture’s analysis of aerial images and maps, historical photographs, property surveys, transcripts of interviews with formerly enslaved persons, and other evidence reveals that plantations conformed to consistent operational logics, determined by the overlapping priorities of a complex which was at once industrial facility, farm, prison, death camp, and luxury estate.

To understand these logics, we built an interactive 3D environment representing what would have been a ‘typical’ sugarcane plantation within the geography of the lower Mississippi River. Because no ‘complete’ plantations remain intact, our modelled environment is a composite of several plantations reconstructed using a wide variety of visual and cartographic evidence.

The case

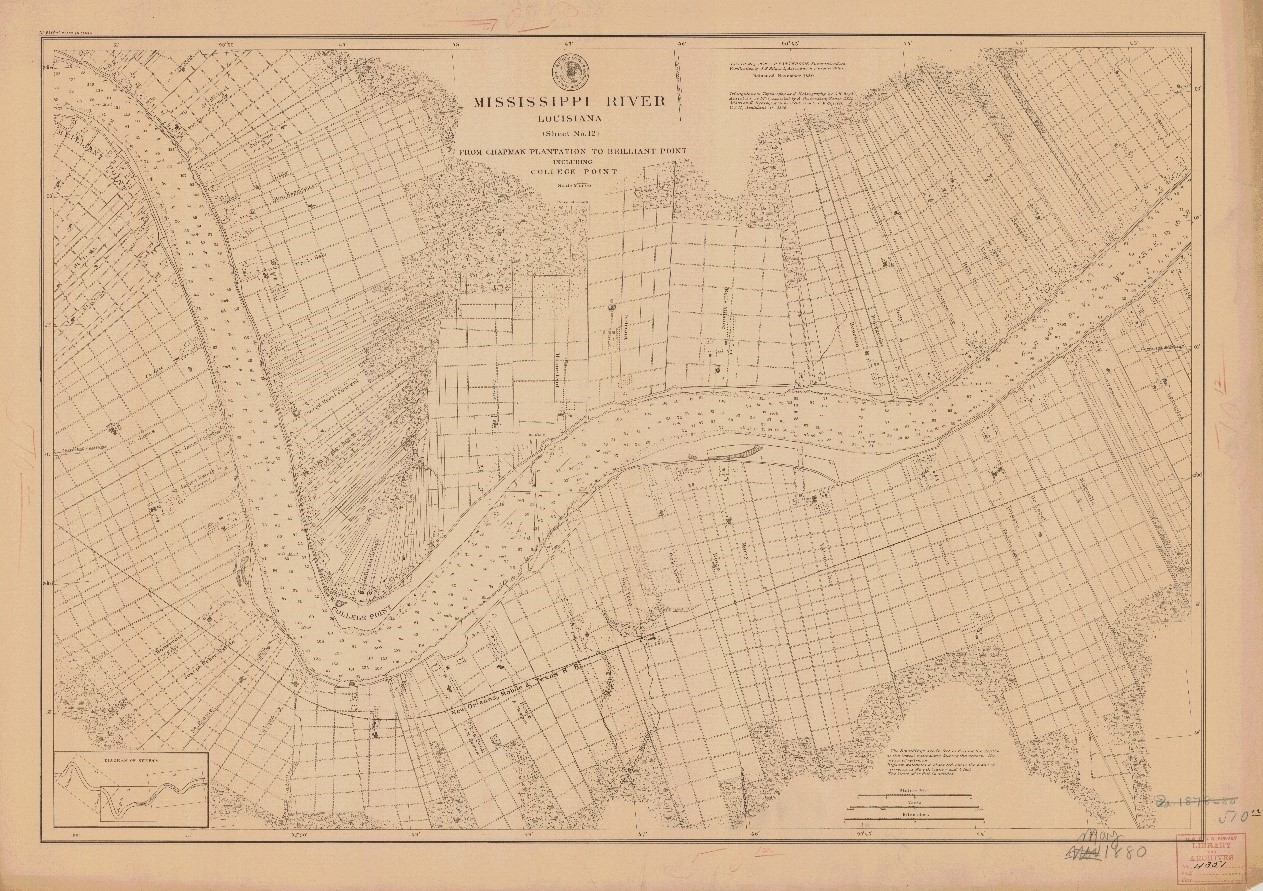

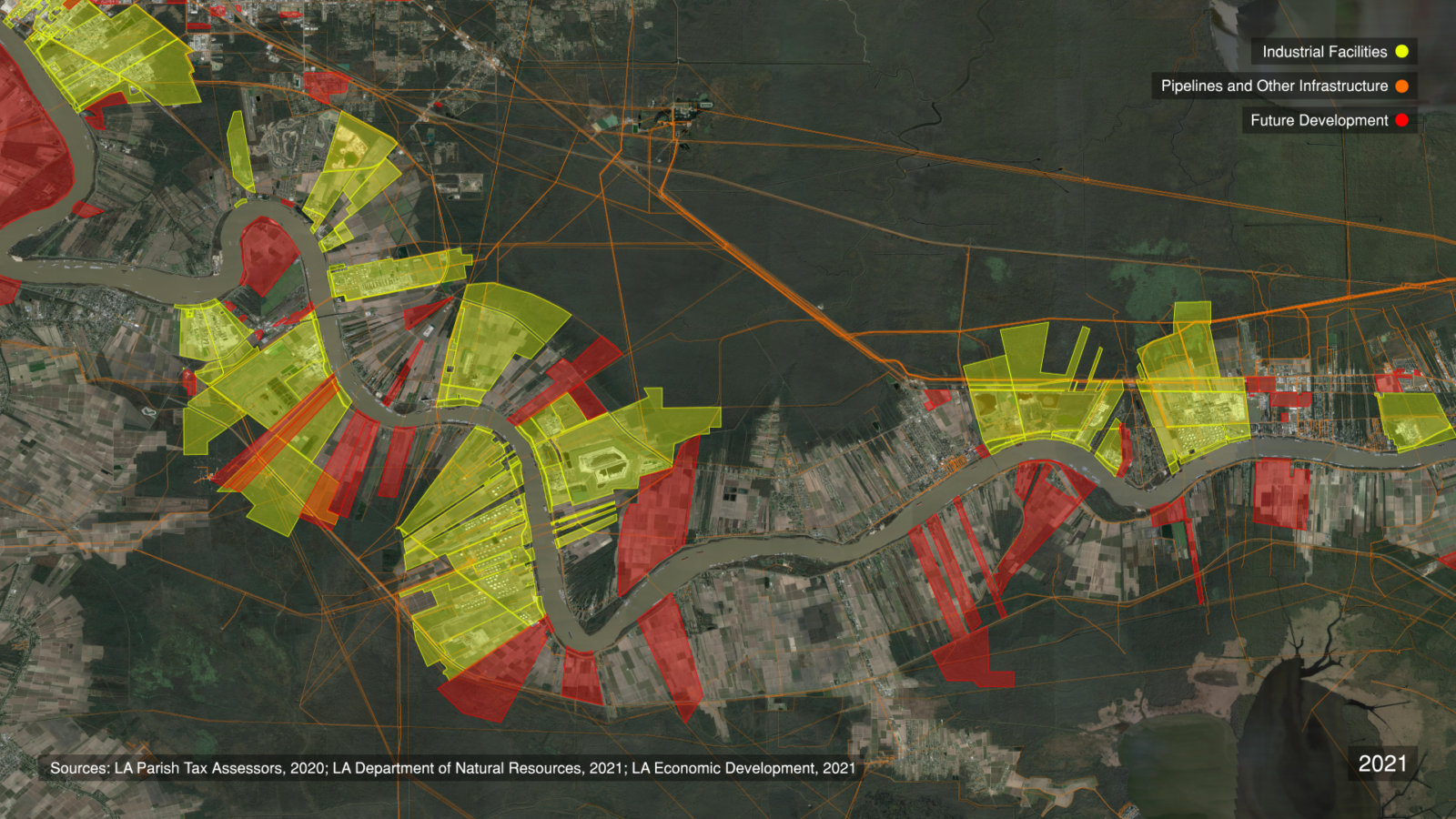

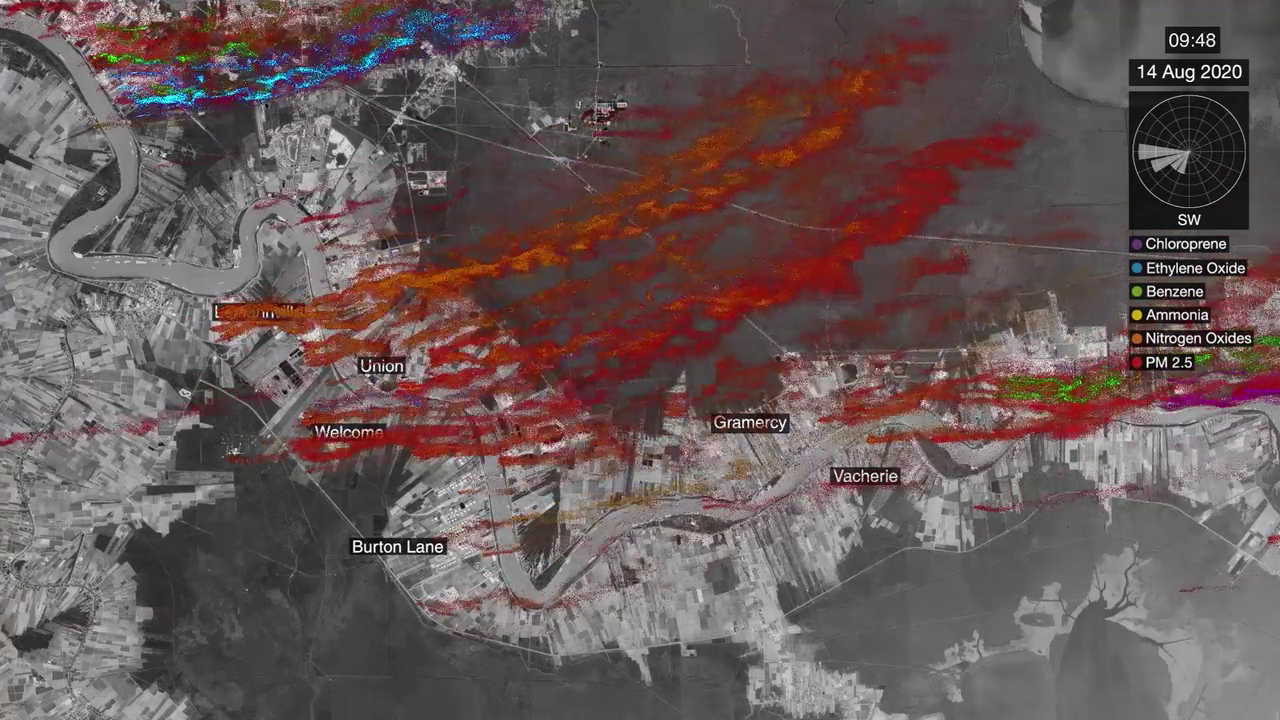

In the US state of Louisiana, along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, a heavily industrialized ‘Petrochemical Corridor’ overlays a territory formerly known as ‘Plantation Country’. When slavery was abolished in 1865, hundreds of sugarcane plantations lined both sides of the lower Mississippi River; today, more than 200 of them are occupied by some of the US’ most polluting petrochemical facilities.

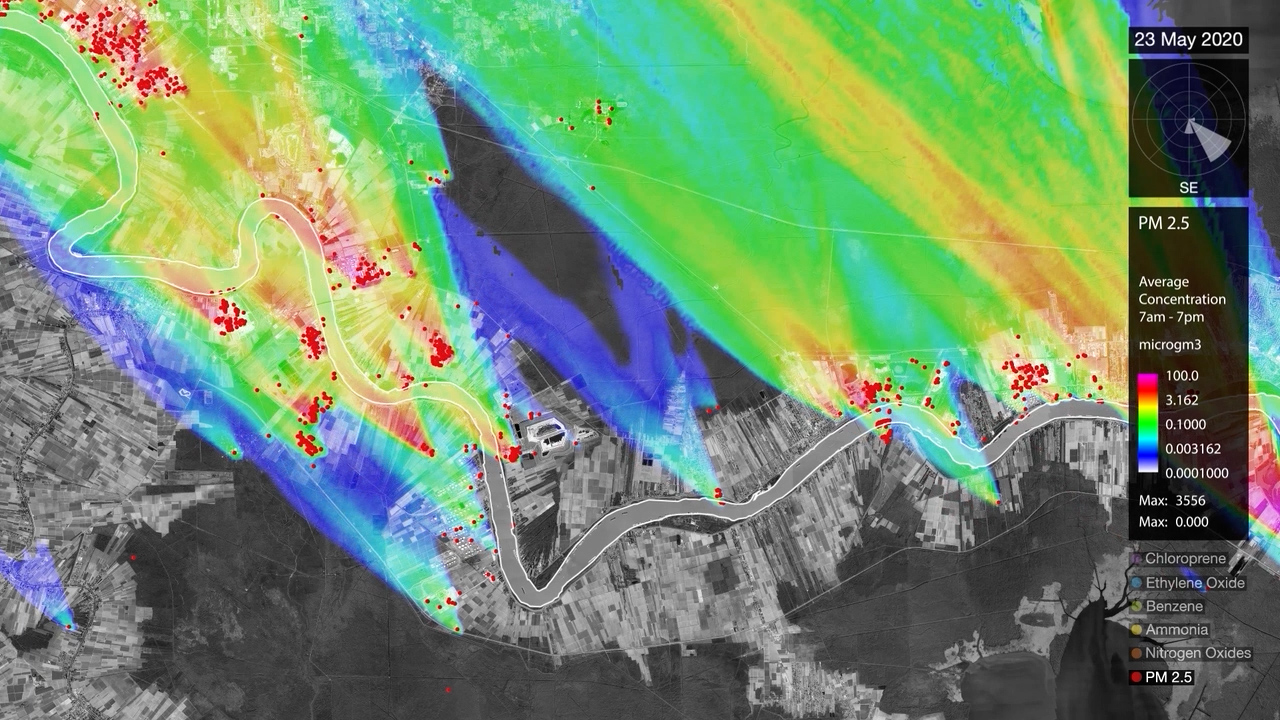

Residents of the majority-Black communities that border these plants breathe some of the most toxic air in the country, and suffer some of the highest rates of cancer and COVID-19 mortality, along with other serious health ailments. Here, environmental degradation and cancer risk manifest as the by-products of colonialism and slavery.

They call their homeland ‘Death Alley’.

A new investigation

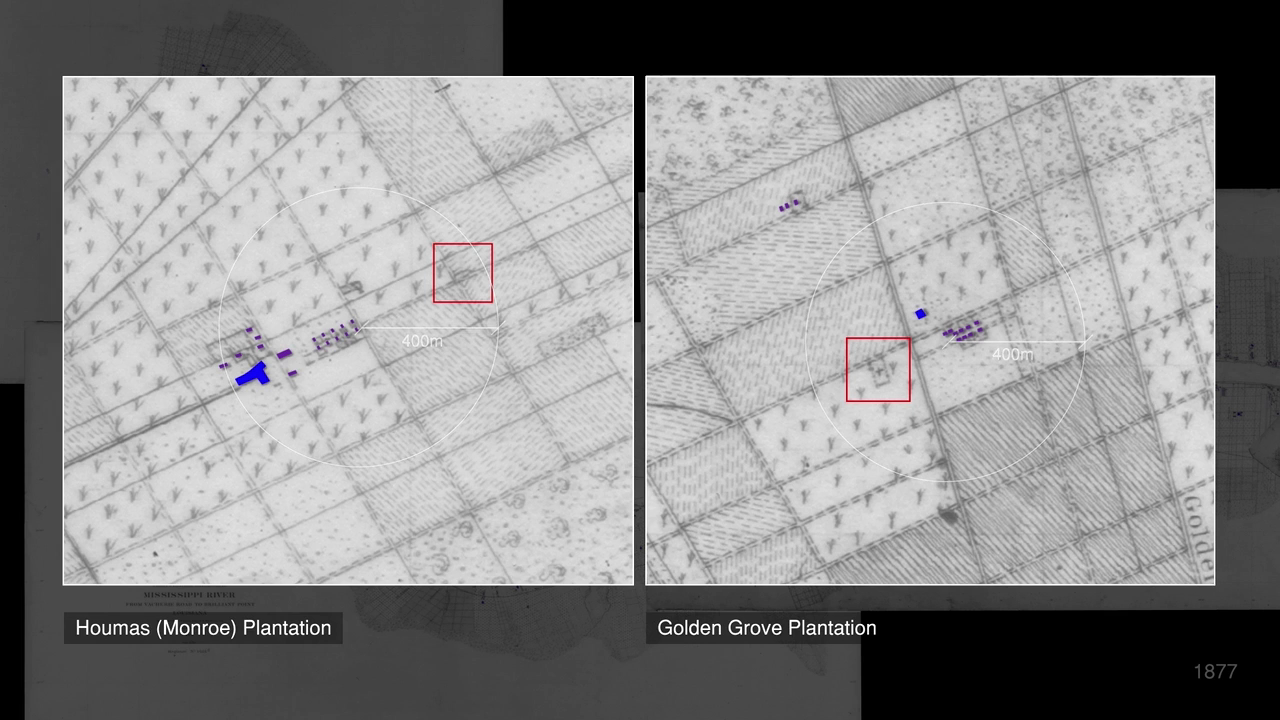

Death Alley contains hundreds, if not thousands, of cemeteries of enslaved people, the vast majority of which are uncharted, and seemingly lost. But the presence of a cemetery can put a stop to proposed development, rolling back the advancing occupation of the region by industrial expansion. FA studied over fifty archaeological field reports commissioned by industry across the region, identifying a systemic disregard for the cemeteries of enslaved people.

The erasure and degradation of hundreds of known, suspected, and unmarked burial sites throughout Death Alley is the result of a persistent racist imaginary that regards Black communities and cultural sites as unworthy of preservation, or worse, as a threat to development. FA’s investigation of over 50 field reports found a systemic lack of regard for antebellum Black cemeteries.

In 2015, two cemeteries were uncovered during a survey for a proposed expansion of a refinery owned by Shell Oil Company. Four years later, four more cemeteries were located during the early stages of the construction of a new facility by the company Formosa Plastics. How might we recover the memory of the hundreds, if not thousands, of missing cemeteries at risk of desecration?

“We used to be able to live off our land—not anymore. Our enslaved ancestors lived, worked, and were buried on these grounds. Now, our so-called representatives want to allow petrochemical companies like Formosa to disturb their only resting places to build more plants that are killing our community. We continue the struggle of our ancestors. Our ancestors want us to live. We want to live.”, says Sharon Lavigne, Founder and director, RISE St. James.

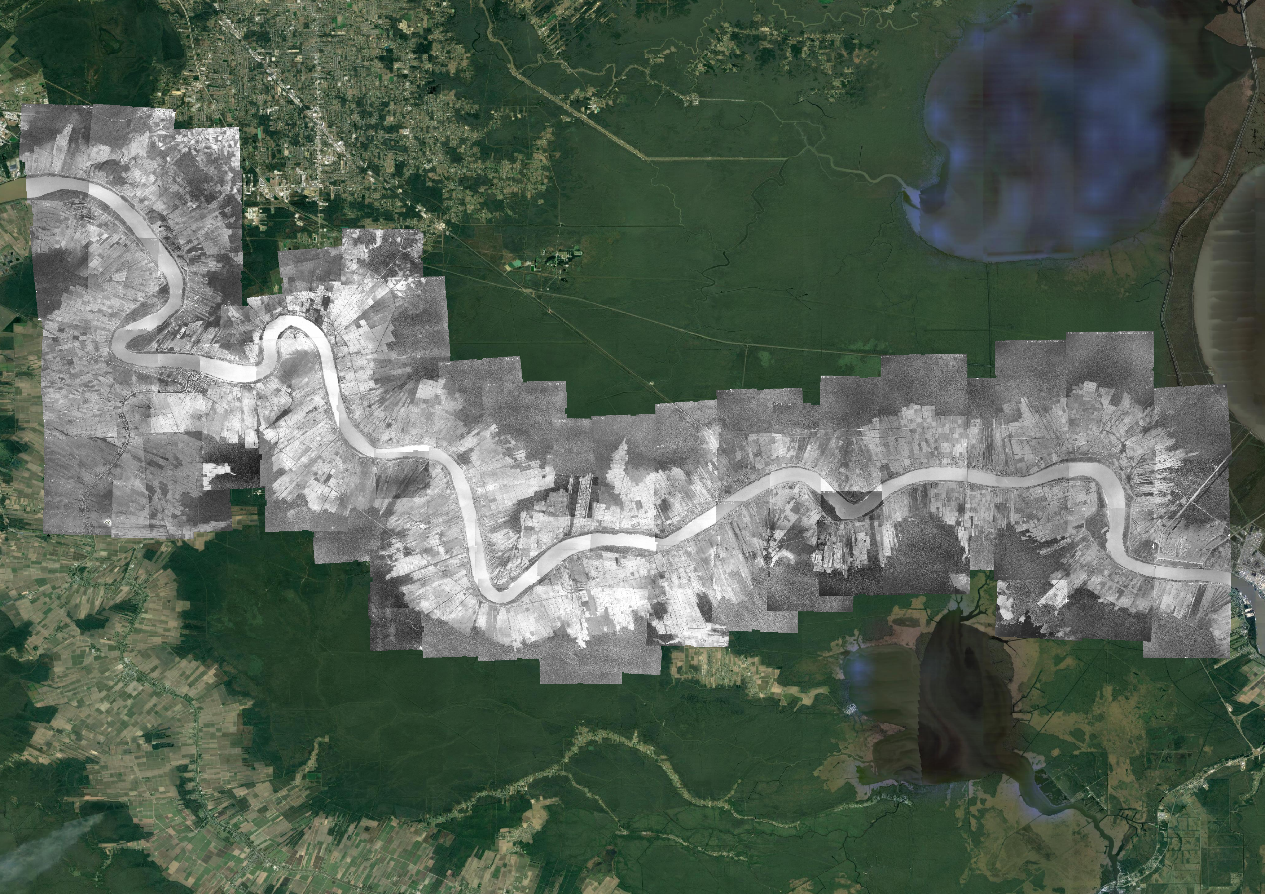

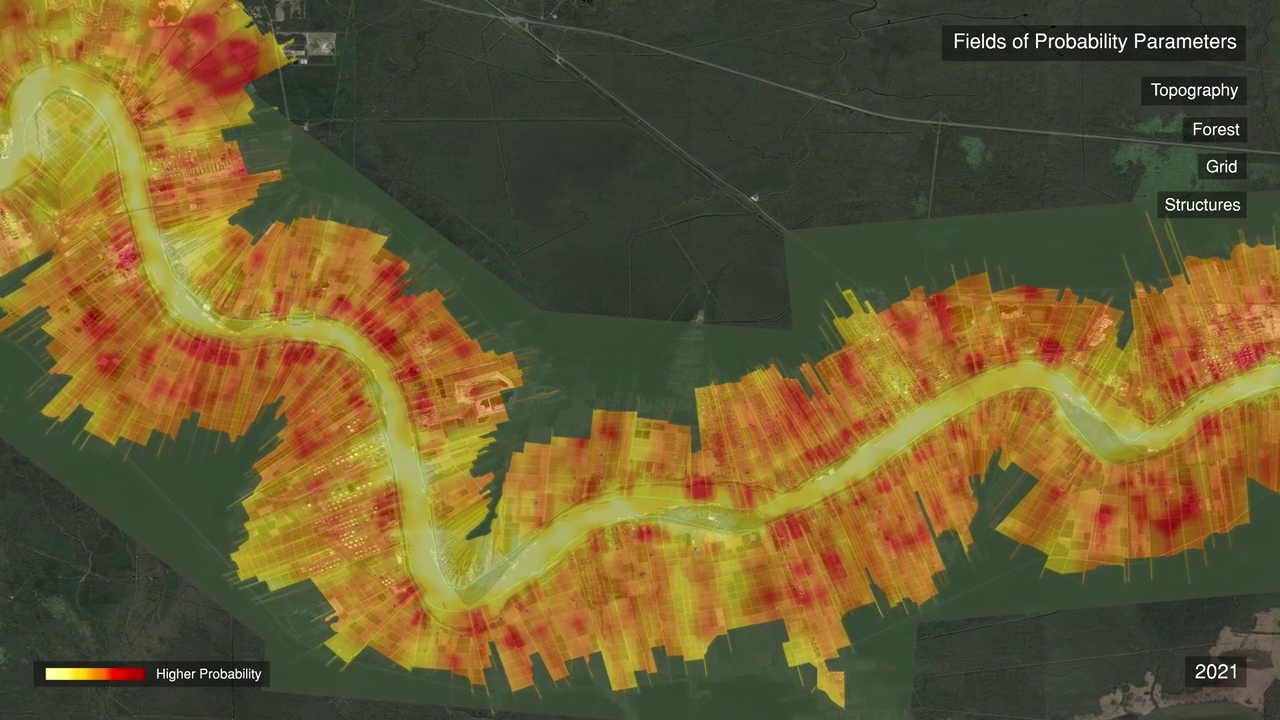

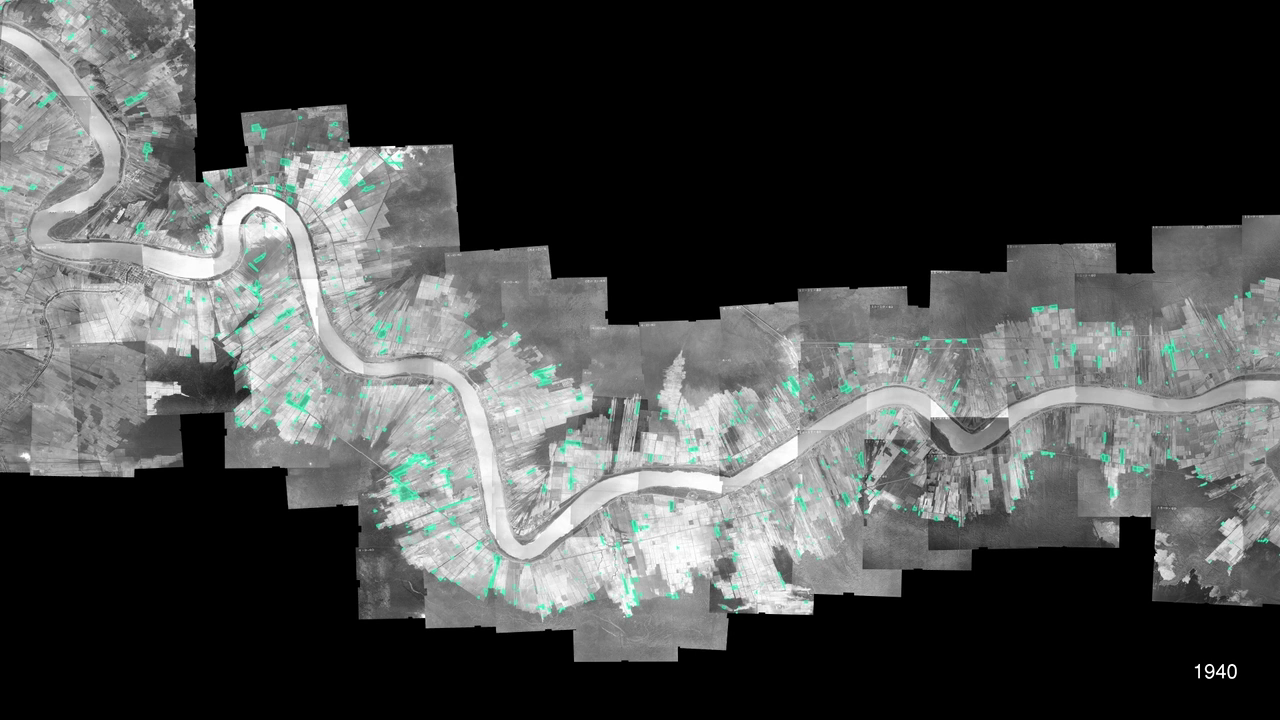

FA’s investigation uses fluid dynamics simulations (provided by collaborators at Imperial College London) to evidence the spread of toxic air pollutants across Death Alley, and proposes a new methodology for estimating the probable locations of cemeteries, drawing on maps and aerial imagery, an analysis of the spatial and economic logics of the plantations, rates of forest clearance, and other historical factors to create ‘fields of probability’ which can contribute to the efforts of the descendant community to recover lost ancestral sites.

“The operational logic of the petrochemical industry in Louisiana includes the intoxication of the air as well as the occupation of the ground. To support the fight of local communities against this industry, we have deployed new investigative techniques, ranging from toxic air simulations to cartographic regressions.”, says Dr Samaneh Moafi, Forensic Architecture’s Senior Researcher.

In the period after the American Civil War of 1861-1865, known as ‘Reconstruction’, emancipated Black people formed small towns, which grew from the slave quarters on the plantations of their former enslavement. Over the course of the 20th century, large-scale industrial facilities have been constructed atop those plantations, and historical ‘freetowns’ have since become today’s ‘fenceline’ communities.

As polluting industry surrounds these communities, it subjects them to another register of racist violence: assault by invisible toxic chemicals.

The Black descendent community has long voiced demands for accountability from the petrochemical corporations that occupy their lands. Our research will be open sourced and made available to the public, to support local claims for accountability and reparations.

“This investigation exposes how the petrochemical industry continues a racialized spatial and environmental logic first established by colonialism and slavery, supports the multigenerational work of Black Louisianans to recover our history and protect our future from systemic erasure. If environmental racism is a monument to slavery, ecological reparations are the only thing that can take it down.”, says Imani Jacqueline Brown, a Forensic Architecture researcher and the project’s coordinator.

Reading the earth

As plantations reorganised life, they also managed death. The spatial logics of the plantation also dictated the siting of Black cemeteries. Slave masters would not sacrifice valuable land for Black cemeteries. Enslaved people were thus interred in uncultivated lands at the back of the plantation, at the ever-retreating edge of the cypress forest. Denied stone, enslaved people often crafted simple wooden grave markers, which naturally decomposed over time. And sometimes, drawing on pan-African traditions, they planted magnolia and willow trees to mark the graves of their loved ones, cultivating ‘sacred groves’.

Sugarcane was a crop of scale; as plantations expanded from the mid-1820s until the Civil War, cemeteries became islands of trees and vegetative overgrowth, isolated amid seas of sugarcane. Clusters of trees or uncultivated patches of land that interrupt an otherwise unbroken topography of agricultural fields are referred to by archaeologists as ‘topological anomalies’.

Through our research, we have found that some anomalies are the ruins of slave quarters or industrial sugar factories. And some are revealed to be the cemeteries of the formerly enslaved. In the years after emancipation, the region underwent a process of spatial, economic, and social Reconstruction. Some cemeteries remained in continuous use, while others were lost to time. As industrial development has expanded, many of the anomalies we identified have been erased.

Conclusion

Through the lens of the petrochemical plantation burial ground, Death Alley is revealed as a 300-year continuum of environmental racism. To confront that continuum, the whole ecology of the region must be considered of utmost cultural value: from the fields where the enslaved were born, worked to death, and buried, to the surviving forests, which under the cover of night became sites of ritual, mourning, and liminal freedom, to Black descendant communities who deserve to inherit far more than a legacy of violence, discrimination, and erasure.

The Black descendent community has long voiced demands for accountability from the petrochemical corporations that occupy their lands. Today, this demand is building into a broader vision of justice: reparations for centuries of racist violence, the repair of the environment, jobs that sustain their communities and their health, a moratorium on industrial development, and agency over how their land is stewarded. Moreover, they demand a fundamental revision of the concept of historic preservation toward a recognition of Black communities, ancestral sites, and our wider ecologies as intrinsically valuable, indivisible, and worthy of protection.

Exhibition

The launch of this investigation coincides with the opening of the exhibition Cloud Studies (2 July – 17 October), which draws together some of FA’s previous and ongoing investigations to explore how states and corporations weaponise the air we breathe to suppress civilian protest, to maintain and defend violent border regimes, and empower extractive industry, including investigations from Palestine, Lebanon, UK, Indonesia, and the US-Mexico border.

The investigation ‘Environmental Racism in Death Alley, Louisiana’ premieres at exhibition Cloud Studies at the Whitworth, Manchester, as part of the Manchester International Festival.

About RISE St. James

RISE St. James is a faith-based grassroots organization formed to advocate for racial and environmental justice in St. James, Louisiana, formed in 2018 after Formosa Plastics announced the construction of a new, 3.5 square-mile plastic production facility – the so-called ‘Sunshine Project’ – that would overshadow Welcome, the community that RISE’s founder Sharon Lavigne calls home.

About Forensic Architecture

Forensic Architecture (FA) is a research agency, based at Goldsmiths, University of London, investigating human rights violations including violence committed by states, police forces, militaries, and corporations. FA works in partnership with institutions across civil society, from activists, to legal teams, to international NGOs and media organisations, to carry out investigations with and on behalf of communities and individuals affected by conflict, police brutality, border regimes and environmental violence.

Facts & Credits

Project title Environmental Racism in Death Alley, Louisiana

Typology Research project, spatial investigation

Methodologies 3D Modelling, Pattern Analysis, Remote Sensing, Fluid Dynamics, Cartographic Regression

Location Death Alley, Louisiana, USA

Date of release July 2021

Research Forensic Architecture

Forensic Architecture Team Project Coordinators: Imani Jacqueline Brown, Samaneh Moafi, Research: Dimitra Andritsou, Olukoye Akinkugbe, Omar Ferwati, Ariel Caine, Research Assistance: Kishan San, Nicholas Masterton, Nour Abuzaid, Sanjana Varghese, Ayana Enomoto-Hurst, Ana Lopez Sanchez-Vegazo, Caterina Selva, Jacob Bertilsson, Video Editing and Production: Sam Blair, Research Support: Robert Trafford, Project Support: Elizabeth Breiner, Sarah Nankivell, Project Supervision: Eyal Weizman

Partners RISE St. James

Additional funding Manchester International Festival, The Whitworth

Collaborators Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), The Descendants Project, Earthworks, Healthy Gulf, Imperial College London, Louisiana Bucket Brigade, The Human Rights Advocacy Project (HRAP), Loyola New Orleans College of Law, The Ethel and Herman L. Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies, Louisiana Museum of African American History, Whitney Plantation Museum

Exhibitions Cloud Studies, The Whitworth, Manchester, United Kingdom (Duration 02.07.2021 – 17.10.2021)

READ ALSO: Porteles_an intergenerational Welfare Complex by MAZi Architects | 1st distinction_National Architectural competition