Text by Ivi Diamantopoulou

Several years ago, when Peter Sloterdijk’s first volume of Spheres first became available in English, I found myself rethinking a lineage of seemingly playful bubble-like inflatable projects, among which ANT Farm’s Clean Air Pod, Buckminster Fuller’s Dome over Manhattan, and Hans Hollein’s Mobile Office. I was at the time contemplating how we barely ever use the noun bubble with verbs that place us outside of it. We often say, “She/He’s living in a bubble!” for example, and the message is unequivocal: the subject has placed itself within a dreamy, unrealistic environment.

The bubble in this scenario is somewhat descriptive of an invisible protection mechanism, disconnecting the enchanted inhabitant from the subjectively unfortunate and cruel reality of its exterior. It stands as the physical manifestation of an illusion, a pseudo-reality that by definition lacks permanence and solidity. But, really, once one looks closer, these mechanisms in fact promote new ideas on autonomy, inter-connectivity, and sustainability beyond the realm of utopias. The question should perhaps be: What is happening outside the sphere that each one of these projects proposes, and can new modes of development emerge from these microenvironments?

Closed Worlds tackles these matters and expands on them through the careful juxtaposition of an extensive body of projects, some more strictly “architectural” than others, that transcend the specifics of tectonics, materiality, and historic context.

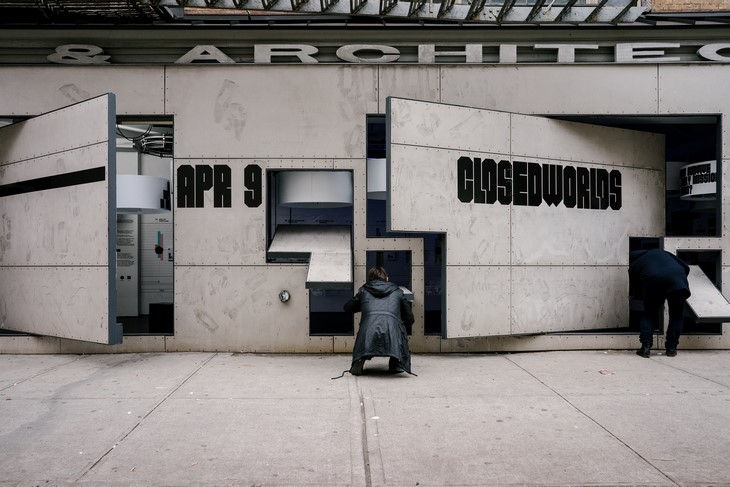

In the nonetheless physically permeable space of the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York, on Tuesday February 16th the curator Lydia Kallipoliti introduced at least a couple of hundred of us (architects, designers, architecture nerds and enthusiasts) to Closed Worlds. The exhibition presents 42 examples of “closed systems,” which she defines as: “Self-sustaining physical environments demarcated from their surroundings by a boundary that does not allow for the transfer of matter or energy.”

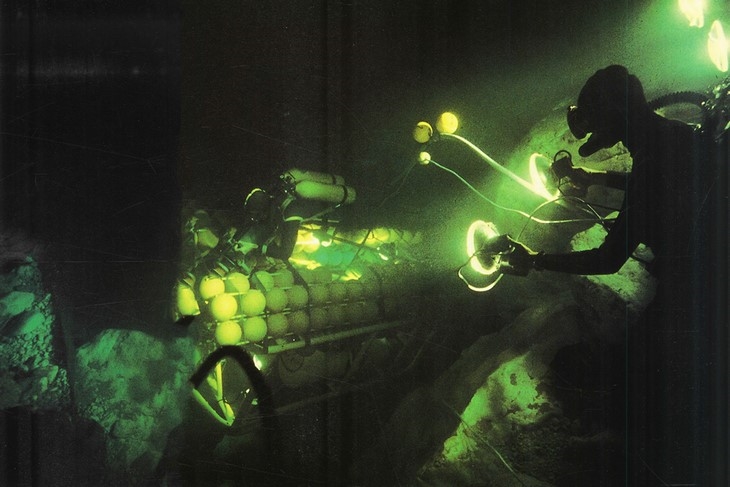

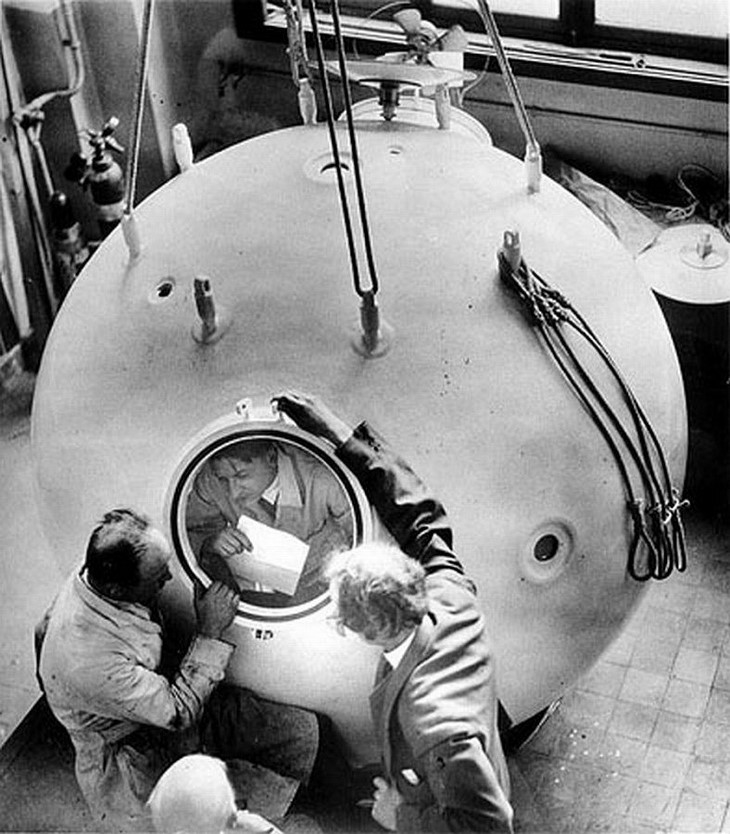

The range of work that fits this definition is unexpected and refreshing. Alongside the above-mentioned inflatables, the material stretches from August Piccard’s FNRS Balloon, an aluminum gondola tied to a massive hot air balloon -the first object to reach the stratosphere; to Alison and Peter Smithson’s House of the Future, a prototype with a perfectly controlled sterilized interior; and Grimshaw Architects’ Eden Project, a contemporary indoors garden built in preparation of extreme global warming. Other highlights include Jacques Cousteau and Emily Gagnan’s Aqualung, a device that made it possible for divers to be underwater for extended periods of time; and NASA’s Langley Simulator, known as the NASA Living Pod, an experimental mock environment designed with the ambition to sustain the lives of four astronauts for an entire year.

The ingenuity of the exhibition lies precisely in its pointed definition of “Closed Worlds,” which allows Kallipoliti’s curatorial agenda to be all-inclusive and perhaps even exhaustive, without lacking specificity. It brings together projects of varying typologies commonly thought of in isolation (say shell structures, inflatables, space architecture, or utopias and so on) presented as a cohesive gamut over a novel common denominator -their ability to produce ecosystems, the other of worlds within worlds, real, projected and speculative.

Historically, 41 of the prototypes examined in Closed Worlds span exactly eight decades, from 1928 to 2008, whereas the 42nd is an interactive installation by Farzin Farzin, designed specifically for the exhibition. Any given pair of projects picked lightheartedly from this show would alone showcase a unique kind of diversity. Hans Hollein’s Mobile Office for instance was only made possible by the use of a vacuum cleaner tube as a ventilation apparatus, whereas NASA’s Living Pod was the product of a highly sophisticated interdisciplinary collaboration of experts such as medical practitioners, chemical engineers, physiologists, food technologists, microbiologists, analysts and architects.

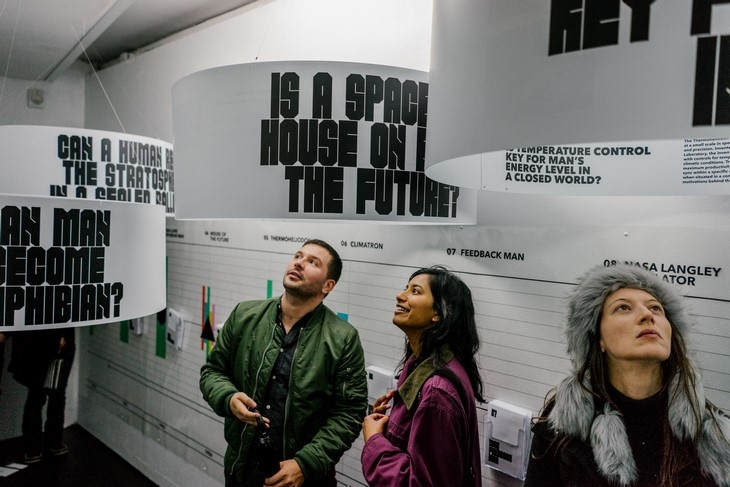

This comparison should give one a good grasp of the multiple levels of diversity between projects, in this case ranging from low to high tech approximations of synthetic self-sustained atmospheres. The exhibition design resembles an open and accessible archive with every project appearing twice. First, the 41 projects are scattered across the space as autonomous exhibits, each one contained in an extruded circle (a closed shape, of course) and hovering over the visitors’ heads. Hung in different heights and marked with the exhibition’s distinctive fonts, their installation creates a delightful landscape across the space, but most importantly their arrangement forces visitors to focus on each project separately without looking at the next.

The way the material is organized within each circular display is highly systematized: key question – descriptive text – archival images – original drawings that illustrate the ways in which it performs. This strict taxonomical process offers unique insight into a conceptual comparative reading of the projects. Along the rear wall of the Storefront for Art and Architecture, all prototypes are brought together as part of a large-scale index.

A result of the close collaboration of Kallipoliti with Pentagram’s Natasha Jen, the diagram organizes the works chronologically and compares their performance and typical characteristics in a straightforward, quantitative way. Instead of an exhibition catalog, visitors are welcome to pick up brochures for each of the projects, an element that adds to the individual experience of this new archive put on display. I, for one, being the diligent nerd that I am, tried to collect them all, and in this effort came to realize that the stacks were circulating in different speeds. I immediately thought this was absolutely fascinating. It taught me, and it may have only been momentary, but that evening Walt Disney’s Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT) was the most popular project in this show.

Closed Worlds, curated by Lydia Kallipoliti, will be at the Storefront for Art and Architecture until April 9th 2016. Read more on the exhibition website here.

The history and future of closed worlds was discussed at Closed Worlds: Encounters That Never Happened, a public conference jointly presented by the Storefront for Art and Architecture and the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture of the Cooper Union. See a list of participants and watch videos of the conference here.

Browse the Closed Worlds Lexicon here

Closed Worlds Exhibition

Curator and Principal Researcher: Lydia Kallipoliti

Research: Alyssa Goraieb, Hamza Hasan, Tiffany Montanez, Catherine Walker, Royd Zhang, Miguel LantiguaInoa, Emily Estes, Danielle Griffo and Chendru Starkloff

Graphic and Exhibition Design: Pentagram / Natasha Jen with Melodie Yashar and JangHyun Han

Feedback Drawings: Tope Olujobi with Lydia Kallipoliti

Lexicon Editor: Hamza Hasan

Special Thanks: Bess Krietemeyer, Andreas Theodoridis, Cecilia Ramos, Alex Miller

42nd Prototype, Some World Games:

Installation Design, Concept, and Fabrication: Farzin Farzin (Farzin LotfiJam, Sharif Anous, John Arnold)

Fabrication Assistance: Joseph Vidich, Kin & Company

Lighting Design Assistance: Christopher Adam Architectural Illumination Engineering

Support

This exhibition is supported by the Graham Foundation and the New York State Council for the Arts. The research for this exhibition has been supported by Syracuse University School of Architecture and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

42nd Prototype 3D printing resources provided by MakerBot.

3D printing provided by Voodoo Manufacturing.

General support for Storefront exhibitions is provided by the New York State Council for the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, Arup, KPF, Sciame Construction, DS+R, and ODA.

*Ivi Diamantopoulou is an award winning architect, designer and writer based in New York City. She received a Diploma in Architecture and Engineering from the University of Patras and a Masters in Architecture as a fellow at Princeton University, where she was awarded the Suzanne Kolarik Prize for Excellence in Design.

Cove photo: Clean Air Pod, Ant Farm, Berkeley, California, 1970, Closed Worlds, 2016. Curated by Lydia Kallipoliti. Storefront for Art and Architecture

CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE, PHOTO BY JAKE NAUGHTON

CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE, PHOTO BY JAKE NAUGHTON CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE, PHOTO BY JAKE NAUGHTON

CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE, PHOTO BY JAKE NAUGHTON CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE, PHOTO BY JAKE NAUGHTON

CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE, PHOTO BY JAKE NAUGHTON CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE, PHOTO BY JAKE NAUGHTON

CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE, PHOTO BY JAKE NAUGHTON BIOSPHERE II, SPACE BIOSPHERES VENTURE, TUCSON, ARIZONA, 1991, CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE

BIOSPHERE II, SPACE BIOSPHERES VENTURE, TUCSON, ARIZONA, 1991, CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE THE ARK FOR CAPE COD, THE NEW ALCHEMISTS, CAPE COD, MA, 1976, CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE

THE ARK FOR CAPE COD, THE NEW ALCHEMISTS, CAPE COD, MA, 1976, CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE, PHOTO BY JAKE NAUGHTON

CLOSED WORLDS, 2016. CURATED BY LYDIA KALLIPOLITI. STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE, PHOTO BY JAKE NAUGHTONREAD ALSO: EDGAR DEGAS: A STRANGE NEW BEAUTY EXPLORES THE ARTIST’S RARELY SEEN MONOTYPES IN MOMA, NY