The reason behind this lecture was our trip to China in December 2012. In that trip, we came in contact with a different culture and we had a first-hand look into the radical changes that are taking place in this distant country. The example of China, the country that would sacrifice anything in the name of modernization, seemed to be the perfect example for us to reflect on with the terms of regionalism, modern architecture and reference to tradition. That reflection is the main idea in our research project.

Xiangshan campus, Hangzhou

In 2000, the Academy of Art decided to place its new campus at the eastern edge of south Hangzhou’s mountains, and not at the zone of higher education institutions approved by the government. Despite the lack of infrastructure, the teachers of the academy, artists and architects, who made this decision all agreed that, according to Chinese tradition, when the time comes to choose the proper place for education, the natural landscape is more important than architecture. The location surrounds a 50 meter high hill called Xiang.

Two small creeks run down the mountain and merge/join at the eastern edge of the hill before flowing into the QianTang river. The landscape is complemented with dense vegetation, which is an unexpected surprise. The academy’s design is divided into two phases: in its northern part that was completed in 2004 and includes ten buildings and its southern section that was completed in 2011 and includes ten more buildings. The third phase of construction has already been started.

As a first impression, one understands that all the buildings unfold around the hill and follow the lines that nature has defined through the small rivers. Buildings of a similar scale but different materials rise next to one other. Every one of them constitutes a unit that is disconnected from the others, yet at the same time they all form an indivisible unity. Such an immediate contact with nature creates a kind of sensitivity and an admiration for the buildings themselves. Following the main road of the campus and having the built part on one side and the hill on the other, we felt that that street didn’t form a border between them. The hill is on our right and the central library is on our left, while we heard the sound of the river flowing by our feet. We actually felt as a part of a living space where nature exists along with buildings in harmony, a relationship between the artificial and the natural, where they highlight and enhance one another.

Cement, metal, brick, traditional black roof tiles and stones, wood, bamboo, glass and reused materials from traditional structures of all kinds create a wide palette of materials here. As an answer to the large scale demolitions that have been taking place in China the last few years, over seven million pieces of old bricks and roof tiles of different decades from the surrounding area were gathered here for the building of the campus. The bricks and the roof tiles that are elsewhere considered useless are reused here. Every building is different. By using some of the above materials, a unique architectural expression is created for every building, but every one of them converses with those around it.

The first phase expands on the northern side of the hill, creating a band of independent concrete structures that consist of nine buildings that are connected to one another by walking routes. In the center of those buildings, three of them stand out with an identical top view. This typical top view is a rectangle, “cut” by a square-shaped garden, giving the building a Π shape. The exterior square space is the main courtyard, providing a view of nature. It is clear that the Π-shape typology is used here for the optimal insolation and ventilation of the whole building.

The buildings of the first phase are building typologies embedded in nature. In our eyes, the typical floor plan and the use of wood brought to mind the organization of a monastery and its relationship with the natural environment. As we moved into the space, we realized that the hill becomes a benchmark, and it remained in sight even through the interior of the buildings. The building seems to have been designed so as to create different perspectives of nature.

In the second phase (2007-2011), by observing the thirteen buildings that are located at the northern side of the mountain, it becomes easy to understand “evolution” in Wang Shu’s architectural vocabulary. In contrast to the first phase, the ground plan is more complicated, and unexpected relationships are created between the buildings and the landscape. The entire complex is pierced by elevated walkways that move around and through the buildings, matching together as a whole and offering a practical and continuous movement from one place to another.

The composition is denser and the buildings are placed closer to each other. The techniques and materials are diverse and the whole composition is characterized by variety. The architectural stroll converses with the area’s slopes and traverses them; a stroll that sees the natural landscape on one side and the built architectural setting on the other. Most of the roofs are flat, while many have classrooms and even outdoor lounge areas built on top of them, creating a city at a higher level. Wang Shu himself mentions:

«When I designed this major project, my main concern was ti integrate the building to the location and implement the osmosis between a contemporary public building on the one hand, and traditional aechitecture and the nature environment on the other ». 1

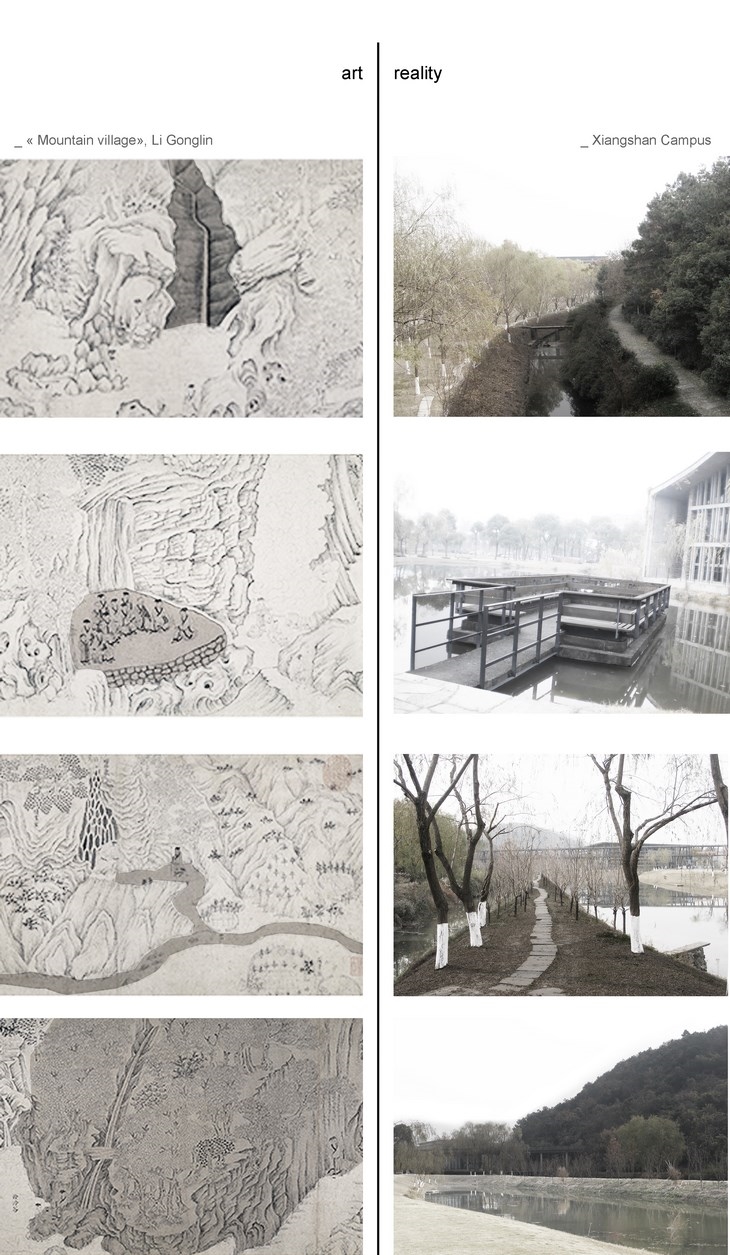

On this topic, it is interesting that the architect compares the designs of the academy with Li Gonglin’s painting «Mountain Villa” and points out how important the art of Chinese painting is to him and that he is able to find architectural elements in it. In this painting, we can discern moments from the daily lives of people and we understand the relationship between the whole and the individual parts that compose it.

Looking at the painting and comparing it with the plan of the campus, we discovered some interesting correspondences. We could divide the two into subsections, each of which would represent different spatial units. In the painting, each of these parts is also a place with different elements. So, we can discern a forest in one part, like the one on the hill at the campus. In another section we can see an opening then succeeded by the element of water surrounded by hills in the center of the composition.

Then, we view a man-made plateau suitable for meditation and relaxation and finally the paths that are carved at the foot of the hill appear.. In the exact same way, the diversity found in the design of the campus with the alternations of the liquid element and the plateaus, the closed blocks and the courtyards, the natural element and the artificial, instills the whole with harmony.

Huamao Art Museum, Νingbo, reference to Chinese Gardens

The city of Ningbo is around 200 kilometers south of Shanghai. It is a major port of the Zhejiang province and has become one of the largest financial centers.

At Ningbo’s economic center, there is a private museum inside the Hua Mao school complex, the most “insignificant” and unpublished work of Wang Shu, since it is not even included in the projects listed on the official document issued by the Pritzker Prize committee. It is a project for a private school in a modern extension of the city of Ningbo that aims to preserve a private collection of traditional Chinese works of art. When one arrives at the museum, a completely different world unfolds before one’s eyes.

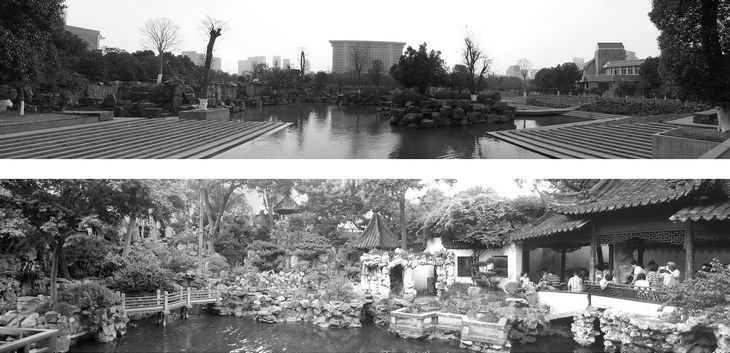

Here Wang Shu creates an entire artificial world. Approaching the museum, we were suddenly inside a garden and saw the imposing building dominating over the surface of the water. The access to the interior of the building is achieved through a two-storey, semi-open space that divides the block of the museum in half. This central courtyard immediately aroused our attention because of the atmosphere created by the calm water in conjunction with the light coming from above through the openings in the roof. The inner courtyard relaxes the eye of the visitor, while the elements of water and nature are in perfect harmony with the museum’s artworks.

Wang Shu creates an entire artificial world, as pointed out above. In front of the entrance and in perfect continuity with the inner courtyard, the water that enters the building creates a large artificial lake. Rocks, trails, stones and plants surround it, creating a setting that initially seemed fake and pretentious to us; it was a representation of a landscape but it had no place among the jumble of skyscrapers. Subsequently, though, we realized that this scenery was nothing but a direct reference to the artificial world created in every traditional Chinese garden.

Lou Qinxi, professor in College of Architecture of Tsinghua University , mentions:

«The art of the chinese garden emphasizes the portrayal of a mood, so that the hills, waters plants and buildings, as well as the special relationship are not just a mere materialestic environment but also evoke a spiritual atmosphere» 2

Walking in a Chinese garden, both small and large, we discovered a completely different environment than what we are used to in European parks. We were confronted by an atmosphere that gave us the impression that we were transplanted into another place. This is precisely the aim of the Chinese garden. Through the creation of forests, mountains and lakes within the city, the poetic quality of nature that drives people away from the madding crowd becomes prominent.

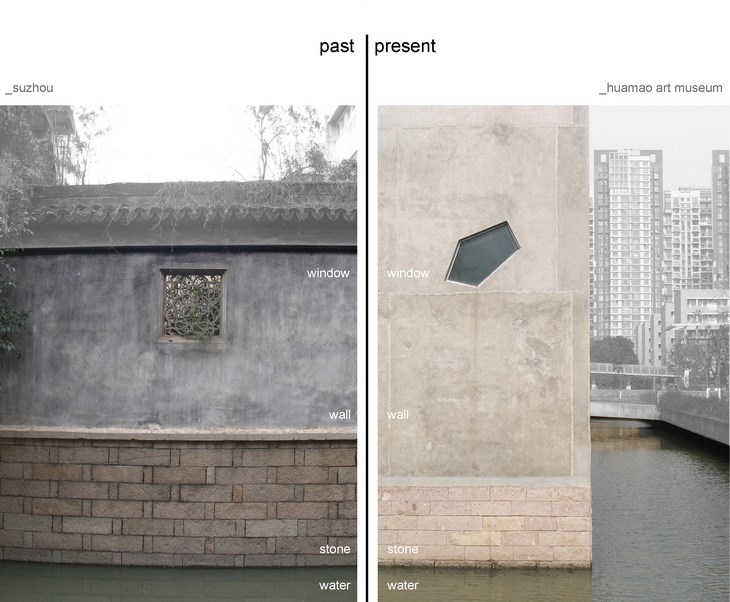

The garden was something special and unexpected during our visit to the museum. It is an artificial landscape unaffected by whatever is happening around it in the modern city and hides quite successfully within the complex of a private school. From the garden of the museum, the building itself looks different. The rough concrete converses with the stones and appears to be like a huge rock over the water. The relationship of the water with the building affects the processing of the façade, which has direct references to corresponding traditional constructions.

In the Hua Mao art museum, the architect does not use traditional materials to invoke memories. A contemporary construction of pure geometry with a modern expression and materials does not give the impression of an association with Chinese tradition. Perhaps a traditional reference that can be found in the building is the repeating triangular apertures, creating a pattern which is found everywhere in Chinese tradition. The patterns are re-interpreted, they become shapes of apertures and they are repeated through the shape and the way in which the natural light enters the building.

These are the only openings on the concrete surface and they reduce the monotony of the rough surface. The modern references that come to the architect’s mind and the visitor`s eyes obstruct the work and one cannot focus on them for too long. What we understand is that in this project, the architect is called to rediscover the elements that he wants to keep in order to unify them in their modern version.

NOTES

1. Wang Shu, Building a different world in accordance with principles of nature, Inaugural lecture at the École de Chaillot delivered by Wang Shu on January 31, 2012. Text edited and translated by Francoise Ged and Emmanuelle Péchenart , English Translation Krystyna Horko, Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, p. 64

2. Chinese Gardens, In Search of Landscape Paradise, Lou Qingxi, China International Press, p. 03

You can read more here

FACADE OF A TRADITIONAL HOUSE IN SUZHOU (LEFT), FACADE OF THE HUAMAO ART MUSEUM (RIGHT)

FACADE OF A TRADITIONAL HOUSE IN SUZHOU (LEFT), FACADE OF THE HUAMAO ART MUSEUM (RIGHT) THE INTERNAL SEMI-OPEN SPACE

THE INTERNAL SEMI-OPEN SPACE MUSEUM?S GARDEN (UP), YU GARDEN IN SHANGHAI (DOWN)

MUSEUM?S GARDEN (UP), YU GARDEN IN SHANGHAI (DOWN) THE FAÇADE OF THE MUSEUM

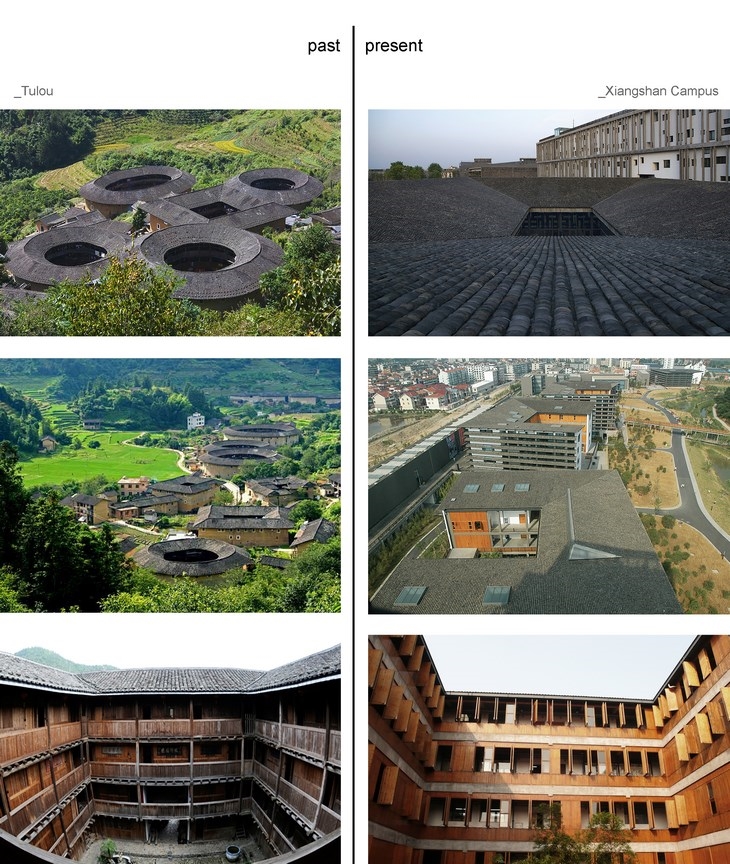

THE FAÇADE OF THE MUSEUM BUILDING OF THE FIRST PHASE COMPARED WITH THE TRADITIONAL TULOU HOUSES

BUILDING OF THE FIRST PHASE COMPARED WITH THE TRADITIONAL TULOU HOUSES SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, XIANGSHAN CAMPUS

SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, XIANGSHAN CAMPUS FROM THE MOUNTAIN TO THE BUILDING

FROM THE MOUNTAIN TO THE BUILDING THE VARIETY OF MATERIALS

THE VARIETY OF MATERIALS MASTERPLAN, XIANGSHAN CAMPUS

MASTERPLAN, XIANGSHAN CAMPUSREAD ALSO: LEGISLATING ARCHITECTURE / LECTURE BY JEAN-PHILIPPE VASSAL: ON FREEDOM, INVENTION & THE POSSIBILITY OF A DIFFERENT URBANISM